Ancient DNA from sled dogs is transforming what we know about how people first migrated across the Arctic and settled in Greenland. These remarkable animals, known as the Qimmeq or Greenland sled dogs, have not only been loyal companions and workers for thousands of years—they also carry a genetic record that traces the journey of humans through one of the world’s most challenging environments.

Recent scientific discoveries show that by studying the DNA of these ancient sled dogs, researchers can map out when and how the Inuit and other Arctic peoples traveled, settled, and adapted to life in Greenland. The findings are changing long-held beliefs, highlighting the resilience of both dogs and humans, and offering practical lessons for conservation and cultural heritage today.

Table of Contents

Ancient DNA From Sled Dogs

| Aspect | Details & Data |

|---|---|

| Breed Studied | Qimmeq (Greenland sled dog) |

| Age of Breed | Genetic lineage traces back nearly 10,000 years |

| Migration Timeline | Inuit and dogs arrived in Greenland 800–1,200 years ago—200 years earlier than previously thought |

| Genetic Groups | Four distinct Qimmeq populations match human settlement regions: north, west, east, northeast |

| Wolf Admixture | No evidence of recent wolf-dog hybridization in modern Qimmeq |

| European Dog Mixing | Minimal European dog ancestry; Qimmeq remained genetically isolated |

| Population Decline | Numbers dropped from 25,000 (2002) to 13,000 (2020) due to climate change and technology |

| Conservation Need | Urgent need to preserve genetic diversity amid modern threats |

| Career/Professional Relevance | Insights for anthropologists, geneticists, conservationists, Arctic historians, and indigenous advocates |

Ancient DNA from sled dogs is more than a scientific curiosity—it’s a powerful tool for understanding how humans conquered the Arctic, adapted to extreme environments, and built lasting partnerships with animals. The story of the Qimmeq is one of resilience, teamwork, and survival, stretching from the Siberian tundra to the icy coasts of Greenland.

As we face new challenges—from climate change to cultural loss—the lessons of the Qimmeq remind us of the deep connections between people, animals, and the land. By protecting this ancient breed, we preserve not just a dog, but a living link to our shared human past.

The Qimmeq: The Arctic’s Oldest Working Dog

Imagine a dog so strong and resilient that it can pull heavy sleds for miles across frozen landscapes, detect seals hidden beneath thick ice, and sleep outside during the coldest Arctic nights. This is the Qimmeq, a breed developed by the Inuit over centuries to be the ultimate working partner in the North.

Unlike many modern dog breeds, the Qimmeq was never bred for looks or as a family pet. Its abilities—strength, stamina, intelligence, and a thick, weatherproof coat—were shaped by the demands of survival in the Arctic. For thousands of years, these dogs have been essential for hunting, transportation, and even protection from polar bears.

The Qimmeq’s Unique Place in History

What makes the Qimmeq particularly fascinating is its genetic purity and continuity. While other sled dog breeds such as Siberian Huskies and Alaskan Malamutes have mixed with different dog populations or been bred for show, the Qimmeq has remained largely unchanged. This is because Inuit communities valued the dogs’ working abilities above all else and maintained strict breeding practices.

As a result, the Qimmeq’s DNA acts like a time capsule, preserving information about ancient migrations, environmental changes, and the close relationship between humans and dogs in the Arctic.

How Ancient DNA Sheds Light on Human Migration

Two Waves of Migration

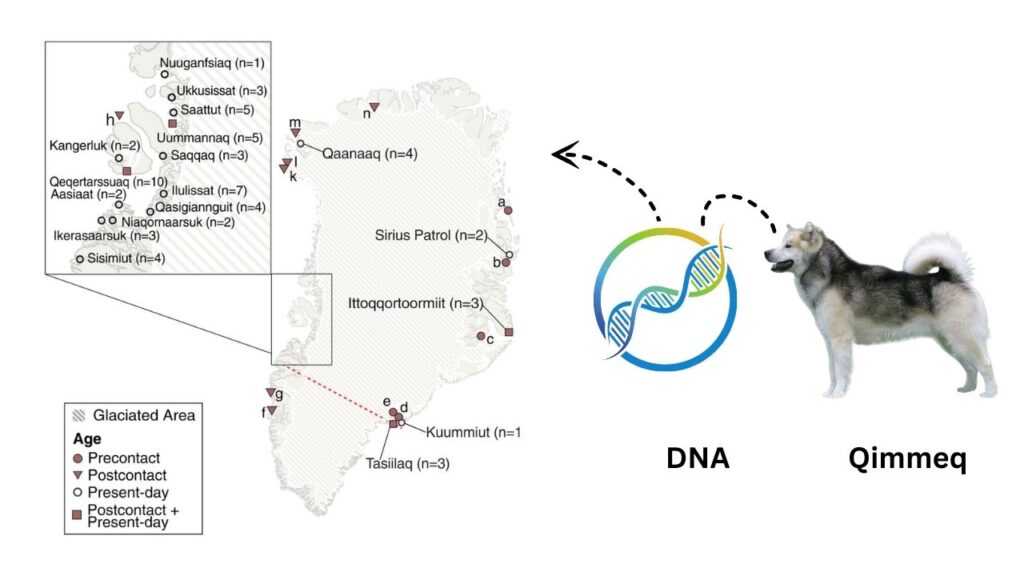

By sequencing DNA from both ancient and modern Qimmeq dogs—some from living animals, others from museum specimens up to 800 years old—researchers discovered evidence of two distinct waves of migration into Greenland from Canada. These migrations began about 1,200 years ago, which is significantly earlier than many previous estimates.

This means that the Inuit, along with their sled dogs, were likely among the first people to settle in Greenland, arriving 200 years before the Viking Norse who are often credited with being early Greenland settlers.

Inuit Arrived Before the Vikings

The new genetic timeline supports the idea that Inuit populations reached Greenland before the Norse. While Viking settlements are well-documented from the late 10th century, the dog DNA suggests that Inuit migration happened even earlier. This challenges the traditional narrative and highlights the importance of indigenous knowledge and oral histories in understanding the true history of the Arctic.

Four Regional Dog Populations Mirror Human Settlements

The genetic analysis revealed four distinct Qimmeq populations in Greenland—northern, western, eastern, and northeastern. These populations match the main regions where Inuit groups settled, showing a close relationship between human communities and their dogs.

For example, in the northeast, both the Inuit and their dogs disappeared in the early 19th century, possibly due to harsh climate events or disease. Later, new settlers reintroduced dogs from other regions, creating a clear break in the genetic record. This demonstrates how dog DNA can reveal even lost chapters of human history.

Lessons From Sled Dog DNA: What We Can Learn

1. Rapid Arctic Migration

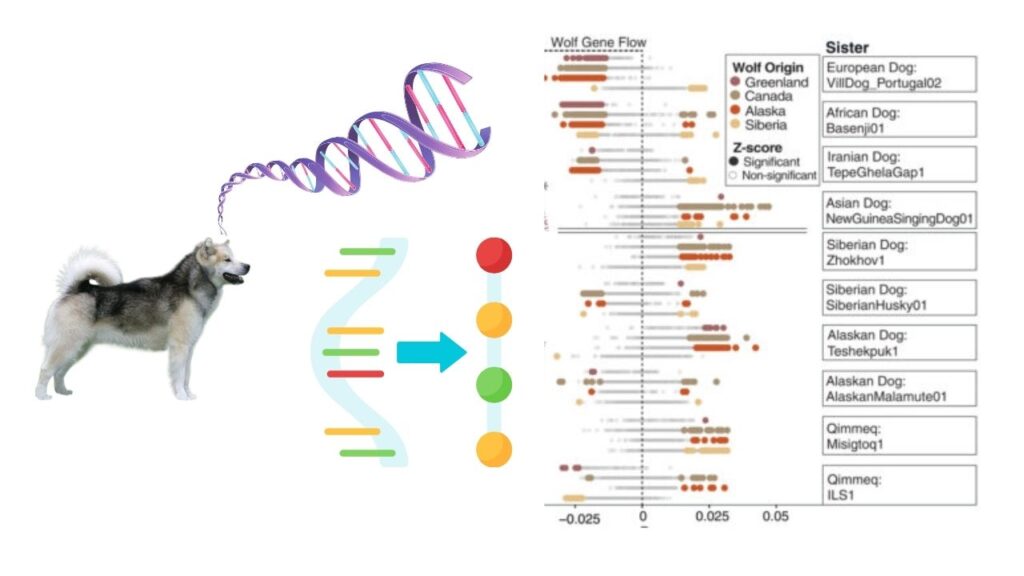

The genetic similarities between Greenland sled dogs and ancient dogs from Alaska and Siberia show that the Inuit migration across the Arctic was fast—possibly taking just 100–200 years. This rapid movement helped the Inuit adapt to new environments and spread their culture across vast distances, using sled dogs as essential partners for travel and survival.

2. Isolation and Genetic Purity

Unlike other sled dog breeds, the Qimmeq has remained genetically isolated. There was very little mixing with European dogs, even after European colonization of Greenland. This makes the Qimmeq a living relic of ancient Arctic life and a valuable resource for scientists studying adaptation and evolution.

3. No Recent Wolf-Dog Hybrids

Despite local legends, there is no evidence of recent wolf-dog hybridization in the Qimmeq. While ancient Arctic dogs do share some DNA with wolves, this genetic signal is ancient and predates their arrival in North America. This finding helps clarify the breed’s origins and dispels myths about its ancestry.

4. Sled Dogs as Historical Witnesses

Dog genomes also captured major historical events—famines, disease outbreaks, and population bottlenecks. For example, the Qimmeq population shrank during periods of famine or disease, mirroring human struggles. Yet, the dogs survived and remained genetically healthy, a testament to their resilience and the strong bond between humans and animals in the Arctic.

The Science: How Do Researchers Study Ancient Dog DNA?

Step 1: Collecting Samples

Scientists collect DNA samples from living Qimmeq using cheek swabs, and from ancient remains such as bones, fur, or skin found in museums and archaeological sites. Careful handling ensures that the DNA is not contaminated.

Step 2: Sequencing the Genome

The DNA is then sequenced, meaning scientists read the full set of genetic instructions for each dog. In recent studies, researchers analyzed 92 Qimmeq genomes and compared them to over 1,900 other dog genomes from around the world.

Step 3: Analyzing the Data

Researchers use computer programs to compare the Qimmeq DNA to that of other dog breeds, both ancient and modern, as well as to wild canids like wolves. This helps them map relationships, trace migrations, and identify genetic changes over time.

Step 4: Interpreting the Results

By linking genetic patterns to known historical events, archaeological records, and climate data, scientists can reconstruct the story of both dogs and humans in the Arctic. This multidisciplinary approach combines genetics, anthropology, archaeology, and indigenous knowledge for a fuller understanding.

The Modern Challenge: Conservation and Cultural Heritage

The Qimmeq Under Threat

Today, the Qimmeq faces new challenges. Climate change, shrinking hunting grounds, and the rise of snowmobiles are all putting pressure on traditional sled dog culture. The population of Greenland sled dogs has dropped sharply, from about 25,000 in 2002 to just 13,000 in 2020.

As snowmobiles become more common, fewer Qimmeq are bred and trained. But snowmobiles cannot replace the unique skills of sled dogs—they cannot sniff out seals under the ice, sense approaching storms, or survive in extreme cold without fuel.

Why Conservation Matters

Preserving the Qimmeq is about more than saving a dog breed. It is about protecting a living link to the past, maintaining traditional knowledge, and supporting the cultural identity of Inuit communities. The Qimmeq’s genetic diversity is also a valuable scientific resource, offering insights into adaptation, disease resistance, and the long-term effects of isolation.

Practical Steps for Conservation

- Support Local Breeders: Encouraging responsible breeding and training of Qimmeq helps maintain the population and genetic health of the breed.

- Promote Traditional Sled Dog Culture: Supporting sled dog races, tourism, and educational programs raises awareness and appreciation for the Qimmeq’s role in Arctic life.

- Collaborate With Indigenous Communities: Working with Inuit organizations ensures that conservation efforts respect local knowledge and priorities.

- Monitor Genetic Diversity: Ongoing genetic research helps track the health of the population and identify any emerging threats.

The Global Impact: What Professionals Can Learn

The story of the Qimmeq offers valuable lessons for a wide range of professionals:

- Anthropologists and Archaeologists: Gain new tools for tracing human migration and cultural change.

- Geneticists: Study adaptation, disease resistance, and the effects of isolation in a unique population.

- Conservationists: Learn practical strategies for preserving endangered breeds and traditional knowledge.

- Historians and Indigenous Advocates: Use genetic evidence to support oral histories and challenge outdated narratives.

Tiny Nanopore Sensor Promises Faster, Cheaper, and More Accurate DNA Sequencing for Everyone

New Diagnostic Tool Can Detect Hidden Cancer DNA Before Symptoms Appear

DNA Enabled Nanostructures Proposed To Achieve Superradiance For Quantum Light Sources

FAQs About Ancient DNA From Sled Dogs

Q: Why are Greenland sled dogs so important to science?

A: Their unique genetic history mirrors human migration and adaptation in the Arctic, making them a “living fossil” for researchers studying both dogs and people.

Q: Did Inuit really arrive in Greenland before the Vikings?

A: Yes, new genetic evidence from sled dogs suggests the Inuit arrived 200 years earlier than previously thought, likely before the Norse.

Q: Are Greenland sled dogs mixed with wolves?

A: No, there’s no evidence of recent wolf-dog hybridization in modern Qimmeq. Any wolf-like DNA is ancient.

Q: What’s threatening the Qimmeq today?

A: Climate change, shrinking ice, loss of traditional hunting, and the replacement of sled dogs with snowmobiles are all major threats.

Q: How can we help preserve the Qimmeq?

A: Supporting conservation programs, respecting indigenous sled dog traditions, and raising awareness about the breed’s cultural and scientific value are all important steps.